ELAR: Reading Study Guide for the TSIA2

Page 3

Vocabulary

Although it involves much more, a significant part of comprehension involves understanding the meaning of single words. Only then can you combine these words with the rest of the text to gain meaning from the entire sentence, paragraph, and passage. The more you read, the more words you “own,” meaning that these words are part of your vocabulary. You may not use them much when you speak, but you can certainly understand them when you read. But having a good vocabulary is only part of it. It is impossible to learn the meaning of absolutely all the words in the world. You will encounter unfamiliar words as you read.

When coming upon an unfamiliar word, or one that has multiple meanings, as you read, it may not always be convenient (or possible) to look a word up in a dictionary. Here are some tips to help you determine the meaning of a word using context clues:

-

Context clues refer to the parts of the sentence around the unknown word, or the sentences directly before and after that sentence.

-

If you come across an unknown word or one that is unfamiliar in the way it is being used, try looking around in the nearby text for any synonyms, implied definitions, or rewording of the unknown word.

-

Replace the unknown word with a blank and see what you can put in that space that still makes sense in the context of the sentence (check for what part of speech is missing; for example, you can’t stick a noun in where a verb needs to be).

-

See if you can apply your critical reading skills to determine an implied meaning. Ask yourself, “What is the author trying to get me to understand with this word?”

-

On a multiple-choice test with answer options provided, you can try plugging in those answer choices and see which one makes the most sense when you reread the sentence using it.

-

Of course, it always helps to rely on the phonics and word decoding skills you learned very early in your reading journey. This may be assessed on the Diagnostic test, only.

Critical Reading Strategies

It is very possible to greatly improve your reading by simply “reading differently.” When you read a book or article for pleasure, it’s possible to just absorb whatever interests you and move on. On the other hand, when you are reading in preparation for answering questions or to seriously glean the author’s message, there are several things you can do to make your reading more productive. Some people call this being a critical or active reader. Here are some suggestions.

Taking Notes

As tedious as it may sound, taking notes while you read is actually a very smart reading strategy. Studies have shown that taking notes while reading helps readers engage with a text on a more complex level. Rather than just having your eyes gloss over the words on the page, active reading through note-taking has you pause, consider, and respond to important or unclear ideas.

Note-taking can take on many forms, and you’ll need to find the ones that work most effectively for you. Notes can be written on sticky notes, in the margins of a text (as long as you have permission to write on it), in a notebook, or on a separate sheet of paper that can double as a bookmark. To be most effective, note-taking should be done as you read a text rather than as a summarizing activity after you read (though that’s another good reading practice).

Although your teachers or instructors might mandate what kind of notes they want you to take, ultimately your notes should be things that are meaningful to you. Consider marking and taking note of unfamiliar words, key ideas, specific terms or dates, questions arising from the text (Where are some places where you are unsure of what the author is trying to say? Are there any places where you would like to ask the author a question?), personal connections you can make to what is being said in the text, or comments you could make regarding what you are reading. Your notes don’t have to be long and involved, just a few brief comments. Jotting down these notes can also help you in the writing stage as your notes will bring you back to specific places in the text to which you can refer.

Response to Text

Your response to a text can be a valuable source of ideas when it comes to writing about a text. As you read, you should include comments about how you are reacting to an author’s claims or what you think about what the author has to say, or to note places where you strongly disagree with an author’s claim. In a fictional text, you may be responding to how you feel about a character, what a character says or does, a plot twist the author might include, or how things turn out (“unbelievable ending! not realistic!”).

Your response to text notes are an opportunity for you to record your initial reactions to a text, jot down questions you have about it, and what your reaction is to the claims made or ideas presented. These comments will help you determine what you really think about what you read and give you some guidance for writing a response to it.

Outlining

Creating an outline as you read can help you to organize ideas and information in a logical pattern which may be helpful for comprehension, as well as responding to a text later. It’s like reaching into the author’s writing process so you can better understand the message. For example, as you make an outline, you are thinking about and examining what the author is doing: “The author wants me to think this, so he/she lists these reasons to convince me”, etc. This type of thing will be helpful if you are later asked to evaluate the author’s presentation, such as telling if the point was proven or if the logic was sound. Remember that note-taking while reading should be quick, so your outline will be just brief notations of what you read.

An outline for a passage might look something like this, with each Roman numeral standing for a paragraph:

\(\text{I. Intro}\)

\(\quad \text{A. Thesis statement}\)

\(\quad \text{B. Other info}\)

\(\quad \text{C. Other info}\)

\(\text{II. Topic}\)

\(\quad \text{A. Evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{B. Evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{C. Evidence}\)

\(\text{III. Topic}\)

\(\quad \text{A. Evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{B. Evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{C. Evidence}\)

\(\text{IV. Topic}\)

\(\quad \text{A. Evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{B. Evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{C. Evidence}\)

\(\text{V. Conclusion}\)

\(\quad \text{A. Any additional info/evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{B. Any additional info/evidence}\)

\(\quad \text{C. Any additional info/evidence}\)

When you read a longer work, such as a book, it might begin like this, with each Roman numeral standing for a chapter or section:

\(\text{I. Chapter 1}\)

\(\quad \text{A. Major event/point}\)

\(\quad \quad \text{1. Minor event/point/info}\)

Then, you would add numerals and letters, as needed.

Summarizing

It is a good idea to take quick breaks from reading to summarize what you have read so far. These summaries can go in your notebook or on the text itself. Summaries can be written at the end of a chapter or the end of a page, or even at the end of a paragraph if the text is very challenging. Summarizing means determining the important points in a text, condensing the ideas, and putting them into your own words. Summaries should still cover all of the main points presented in a text, but should be a briefer writing and avoid including all of the details and specifics. They should not include your personal opinion or thoughts, but just be an objective, big picture “retelling” of what you read. Think of summarizing as how you would explain what you’ve read to someone who hasn’t read it, in 30 seconds or less. Here’s a sample checklist you might use to make sure you have addressed all of the main parts:

- Title/Author—Include the basic information of what you read and who wrote it

- Who/What—Who or what was the reading about?

- But—What was the problem that arose?

- So—How did the character(s) address or solve the problem(s)? What are the ideas for a solution?

- Then—How did things end? What was the resolution?

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is not the same as summarizing. Summarizing condenses but paraphrasing does not, so you will want to paraphrase sparingly. Think of paraphrasing as translating a text into your own words. It is particularly useful when you encounter a part of a text that is difficult to understand because it requires you to thoroughly understand what you have read and can serve as a way to check your comprehension as you read. Then, if you are unable to paraphrase, you may want to go back and reread parts of the text that will help you to understand it better. Just be sure that you are putting the text in your own words—if you copy the original text and its wording, it is considered plagiarism. Be sure to include details and specifics in your paraphrase. Remember, paraphrasing doesn’t require condensing or shortening the original, so you can include those details that you might leave out of a summary.

Using Quotations

Sometimes, an author’s or character’s exact words will help with comprehension of a piece. Just be sure to record them using quotation marks (“) so, if you use your notes to write later, you’ll remember these were not your words and you can cite the source.

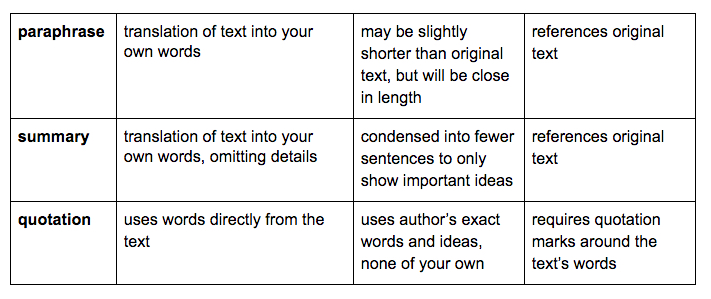

Here is a chart to help you remember the differences between paraphrasing, summarizing, and quoting:

Digging Deeper into the Text

Using the preceding strategies and your best critical reasoning skills, many things will become apparent to you from reading a text—things that aren’t specifically laid out, but require more thought to discover. These are the main things you’ll find.

Thinking as You Read

Beyond just visually reading the words on the page, your brain should be constantly evaluating what you’ve read. This practice will do wonders for your comprehension. Here are some things to consider.

Explicit or Implicit Information

See the above section on this subject and evaluate everything you read to discern what type of information you are reading. Is the author telling you something or are they merely implying the same.

Drawing Conclusions

When we read, we draw conclusions about the material to which we are exposed. Using our previous knowledge and experience, coupled with the new understanding we gain from reading a text, we come to conclusions about the author’s ideas and stance. Conclusions are considered accurate if they can be supported with information that is found in the text. Conclusions should never be drawn based solely on previous knowledge without the incorporation and consideration of the information presented in a text.

Drawing logical conclusions is possible through note-taking, looking for evidence provided in a text, evaluating a text’s credibility, considering what is directly stated as opposed to what is implied, summarizing a text, and/or paraphrasing a text. Using these skills, readers can form their own conclusions about a text and about the author’s message.

Credibility

Credibility means believability. Readers cannot draw accurate conclusions if the sources authors use are not credible or believable. Readers must also question the author’s credibility. Is this person trustworthy? Do they seem to know what they are talking about? Do they present themselves as unbiased and objective? In persuasive writing especially, authors want their audience to believe what they are saying and to trust their claims. Many uneducated people may just blindly accept the claims of an author. But careful, critical readers question the credibility of the author and his or her sources of evidence.

Predictions

Readers use what they read as the basis for making predictions about how this information might work in other contexts. Standardized reading tests often ask you to take information directly presented and formulate predictions. Only credible text and sources should be used as the basis for predictions or the reader may make entirely inaccurate conclusions and apply ideas erroneously to a different context. Considering the facts and details, be sure to contemplate how relevant this information would be in a different situation.

All Study Guides for the TSIA2 are now available as downloadable PDFs