Subtest III: Visual and Performing Arts Study Guide for the CSET Multiple Subjects Test

Page 1

General Information

There are only 13 multiple-choice questions and one constructed-response question about the arts in Subtest III, but the domains covered vary widely. You could encounter questions about any of the following topics: artistic perception, creative expression, historical and cultural context, aesthetic valuing, and the various connections, relationships, and applications involved in the arts.

You will need to use what you know about the topics contained in the California state framework for arts education to discuss artistic products. We have given you an outline of some of the basics contained in this resource below, but to learn more, consult the link above.

The Visual and Performing Arts test applies to all students, even students with vision, hearing, movement, physical, or other limitations.

Important Update

As of August 1, 2022, the test code for the CSET Subtest III: Visual and Performing Arts is 225 instead of the previous 103. The content assessed is the same as that in the previous test version; however, there is now a greater emphasis on practical and technical skills in the arts, including:

- interpreting art

- analyzing the meaning and purpose of art

- evaluating art effectiveness

These changes are designed to increase focus on concepts that can help students become producers or creators of these four art domains. To this end, the test creators assigned three new sub-categories to each domain. They are as follows:

Dance

- movement

- technical skills

- analysis

Music

- elements of music

- musical ideas and connections

- selecting music

Theater

- creating a story

- improvisation and design

- contextual analysis

Visual Arts

- tools, materials, and techniques

- connections and value

- purposes

The Four Domains

The CSET divides the visual and performing arts into four main categories (domains), with three subcategories assigned to each. We will discuss each of these domains in depth, presenting not only the background knowledge you will need to demonstrate on the test but also reviewing specific skills that should be taught to students to encourage their future participation in art creation and production.

Dance

Dance is a kinetic way to express emotion, ideas, or concepts. Dancers perceive external stimuli and create movement.

Dance is normally performed in groups or with partners. Solo or duet dance is usually performed as an introduction to a group dance. On rare occasions, solo dance is used to feature a famous, highly skilled dancer. Most stage dance involves memorizing choreography, which encompasses the dance sequences and steps. Find details about choreography below.

Once a student has mastered the basics, they are trained to:

- keep “in time” with the music

- match what others are doing

Children naturally learn to dance and move rhythmically as a result of observation and mimicry. Age-appropriate (and skill-appropriate) choreography can be taught to students. Dance is often used as part of strength training, and professional dancers are immensely strong.

Movement

Dance exists in the movement of bodies. Without movement, there is no dance. Legs move the body across the floor. Arms reach. Hands grasp. In ballroom dance, the partners hold each other in position as they move. The strongest and most experienced dancers can lift their partners.

Dancing usually includes costumes and can sometimes include props. Interacting with these external elements can help the dancer/student express themselves.

Stimuli

The most obvious external stimulus is music, but other elements can be used to influence the dancers’ interpretations. Teachers should be familiar with a variety of stimuli, including:

- music

- other sounds

- costumes

- props

- projections

- other images

- interactions with other dancers

- other elements

Music/Sound—Music for beginning dancers is rhythmic, with an easily detected pattern. Beginning students should not be asked to puzzle out the rhythm of a complicated song. The meter and rhythm should be obvious. The down beat of the measure (the “one” in a 1 2 3 4 meter) should be easy for a beginning student to find.

The 4/4 time signature is universally used for beginning dancers because of its simplicity: there are four regularly timed beats per measure throughout a piece. Conveniently, the 4/4 time signature is the single most commonly used time signature in western music. Because of this, the 4/4 time signature is also called common time.

Text—A more advanced stimulus is dancing about a word or concept.

As part of an advanced improvisational exercise, an intermediate or advanced student can be asked to use as motivation a provided word or phrase, such as:

- war

- springtime

- life

- death

- swimming

- happiness

Beginning/younger students can also use this technique, but there’s a greater possibility of them becoming self-conscious or embarrassed. To avoid this sort of problem, these exercises are generally best done with an entire class doing the exercise at the same time so no one is singled out. The teacher can also participate.

Although text stimuli are rarely used as a performance technique, they can be used to explore internal feelings or provide insight into an existing choreographed piece. Text stimuli can also be used as part of a group (or individual) warm-up exercise.

Objects—Working with an object can provide a new dimension to performance. As part of the choreography, a dancer or dancers can move an object in various ways by:

- using it cooperatively

- using it competitively

- simulating sports activities

- trying to wrest it away from each other

- playing tug-of-war

- sitting on it

- standing on it

- throwing it back and forth

- wearing it as a mask

- wearing it as a hat

Some objects carry symbolic meanings. Audience members will automatically assign emotional relevance. A company that used objects extensively was the Swiss group Mummenschanz. Mummenschanz was a mime/dance troupe that depended heavily on prop-based mime to express ideas, concepts, and emotions. The troupe was formed in 1972 and started its last world tour in 1995.

Mummenschanz

Mummenschanz. (2022, December 28). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mummenschanz

Images—A dance (and dancers) can be influenced by images projected on the wall, printed on physical cards, or displayed in photographs. This is different from working with an object. Working with an image is rarely about the physicality of the image but rather using it as a stimulus to express an abstract concept or idea.

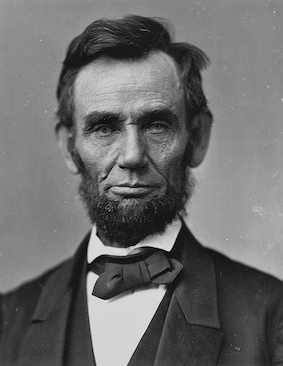

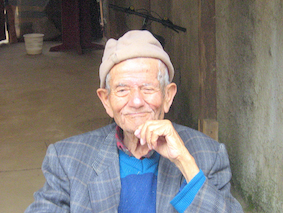

Consider the following two images. Both show the faces of an older gentleman. But if these images were projected on a screen, each would invoke completely different responses in a dancer and/or an audience:

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

16th president of the United States

Abraham Lincoln. (2023, March 2). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Lincoln

A smiling 95-year-old man from Pichilemu, Chile

A smiling 95-year-old man from Pichilemu, Chile

Retrieved from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/46/My_Grandfather_Photo_from_January_17.JPG

Symbols—Symbols can be painted/printed on costumes, painted on objects, projected, shown as photographic prints, held, waved, printed on flags, etc. Anything that causes the dancers (or audience) to attach abstract meaning can be considered a symbol. Symbols are often used to indicate abstract/intangible constructs.

There are many types of symbols:

- religious

- spiritual

- symbols of nature

- coats of arms

- nationalistic symbols

- flags

Students can be trained to recognize symbols presented in dance and other art forms.

Observed Dance—Students learn by watching others dance. The copying of what a child sees is often their first type of dance (mimicry). Often this is done without a teacher being present.

When formal dance instruction starts, a teacher, choreographer, or advanced student will demonstrate a few simple dance steps, then say, “Now, do what I just did.” Dance is, by definition, a visual medium. “Watch and repeat” is a very common instruction technique.

Experiences—A student who has been taught ballet or folk dance will naturally have an advantage when learning choreography, ballroom dance, or other forms of dance. Almost every national culture has a folk dance tradition, with its own dances, music, and culture of expression. Some young students will have been exposed to folk dance as part of their family activities and/or cultural heritage.

Armenian dancers. HlushenkovFolkFest in Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine.

Folk dance. (2023, February 7). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folk_dance

Ballet is often the first formal training that young students receive in dance.

Physical skills in movement are often related. An expert in one form of dance can more quickly learn a new form of dance as compared to a student with no previous dancing experience. Also, an expert athlete can more quickly learn dance than a person with no expert athletic skill. Sports that emphasize grace, balance, and kinesthetic awareness will provide the biggest advantage, including:

- gymnastics

- figure skating

- ice dancing

- diving

Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron—Ice dancing

Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron—Ice dancing

Ice dance. (2022, December 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ice_dance

Dance Improvisation

As a method of free expression, improvisation can allow a student to express themselves. This is best done as a group exercise without the pressure of dancing solo in front of the entire class. You can simply play lively music and start. The teacher might choose to participate with the students.

Improvisation isn’t a good activity for beginning students on their first day. It is best to wait until the students have been introduced to the basics of movement and have learned a few choreographed phrases.

An intermediate/advanced student will be able to improvise a complete dance: beginning, middle, and end. Improvisation remains a good activity, even with advanced students, as a warm-up exercise.

Note: Improvisation is sometimes used to help plan the choreography. Without the entire company being present, the music is played, and the choreographer and a couple of advanced dancers will improvise some movement. These improvisations will help the choreographer to plan, solidify, or embellish the choreography.

Choreographic Devices

Choreography is a sequence of steps and movements. It is preplanned and organized. Normally everyone in the chorus will perform the same steps. (Dancing with a partner is slightly more complicated.)

There may be a soloist (or duet) performing in front of the chorus who will be dancing the same steps or steps in the same theme.

Dancers are often arranged in a pattern. There are two basic patterns:

-

Line—Dancers are arranged in a line facing the audience. This is most commonly used in musical theater or during dance recitals.

-

Set—Dancers are in a circle. This is commonly used for folk dancing, including American square dancing.

There are a few dances that don’t fall into these two patterns, mostly folk dances.

Here are a few examples of how to arrange eight members of a chorus in a line or in a set:

- forming a “chorus line” of eight evenly spaced dancers facing the audience

- forming a “chorus line” of four couples facing the audience

- four couples facing the center (square dancing)

- in a circle, each dancer facing the center, “cascata” (Italian, meaning “cascade” or “fountain”)

- in a circle, dancers following each other around the circle, “procedió” (Italian, meaning “precede” or “follow”)

- in a circle, each dancer facing a partner, “ruota” (Italian, meaning “wheel”)

Generally speaking, choreography is best when every foot is stepping at the same time, every arm is in the same position, and every hand is making the same gesture. Choreography is the antithesis of individual expression—it is a well-planned team effort.

Space

The dance should make good use of the space. The dance should fill the entire stage unless there is a good, artistic reason why the dance should be contained or restricted. An example of restriction: If the dance is portraying the fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, a choreographer could restrict Hansel and Gretel to a tiny portion of the stage to simulate their confinement. If appropriate, a set piece resembling a cage could be placed on the stage to better illustrate this restriction.

With beginning dancers, spread the dance out as much as possible. Sometimes, before recitals for beginning students, numbered dots are painted on the stage to help the youngest dancers find their spots and maintain spacing.

Time, Tempo, and Rhythm

Keeping time and staying with the rhythm are fundamental skills for a student dancer to learn.

The concept will be explained in better detail in the “Music” section of this study guide. But, briefly:

-

Time (also called the beat of the music) is a constant pattern defined by the time signature. In 4/4 time, it is the 1, 2, 3, 4 count that each measure will have.

-

Tempo is the speed of the music, usually expressed in “beats per minute.”

-

Rhythm is the pattern of long and short notes in the music.

The youngest, least experienced dancers can be taught how to “keep in time” using counting/clapping exercises. Every dancer should be able to count the beats of a 4/4 measure and clap the rhythm. A teacher should play the music for the class and help the student find the time and rhythm.

Some pieces of music are faster than others. The students should be able to maintain time with the music, regardless of the speed (or “tempo”) of the music.

Introduce the more advanced time signatures as appropriate:

- beginning students: 4/4 time (common time)

- intermediate students: 3/4 time (waltz)

- advanced students: 2/4 (cut time) and 6/8 (minuet)

Repetition

It is easier to learn a dance when there is repetition.

If a dance has five parts and each part is different, it will be difficult to teach and to learn. If a dance has five parts, and the first two parts use the same sequence of steps, the second two parts use a different sequence of steps, and the fifth part is a repeat of the first sequence, it will be a much easier dance to perform. Its form can be written like this:

- A

- A

- B

- B

- A

However, such a simple dance will not be very interesting for a dancer or an audience member. An age-/skill-level balance will need to be struck between complexity and ease of instruction/execution.

For very young students, a minor variation to a sequence can be made to moderately increase the complexity, such as doing the turns of one part to the left and the turns to another part to the right, or adding minor flourishes, which would look like this in written form:

- A

- A

- B (turns to the left)

- B (turns to the right)

- A (extra movement with the arms)

Energy

The concept of energy is extremely difficult to explain. There is no one thing that can describe or demonstrate the concept of energy. It is, however, very apparent in a performance. A performer that has good energy will go far. A performer that has weak energy will not do well.

There are many things that a performer can do to improve their energy on stage. A performer should use every trick they can to demonstrate good energy. Essentially, though, the audience needs to connect with the performer. There are various ways to do this:

- Be prepared. Know the material. Know the dance.

- Engage with the audience. Stand close to the edge of the stage.

- Maintain eye contact. Look into the audience (if it is appropriate to the performance).

- Laugh at your own mistakes. Don’t try to explain away any issues.

- Look like you are having a good time.

- Don’t scowl or glare.

- Smile.

Smiling is highly important but often neglected, and it accomplishes these things:

- builds rapport with the audience

- conveys confidence

- reduces the performer’s stress

- improves the performer’s attitude

- uplifts the audience

A scowl or a squint conveys a dislike of the audience and/or a lack of confidence on the part of the performer. A look of intense concentration on the face of a dancer does not instill confidence.

Here are two last-minute pieces of advice for the dancers:

-

Remember, the audience wants the dancer to do well.

-

Don’t try to get the audience to like you. Don’t chase the applause or laughter. Do what you do. Let the audience come to you.

Technical Skills

Technical skills are the collection of tools and abilities that allow a dancer to move on stage. When a dancer is said to have good technical skills, they move easily, with grace and precision. It is important that a teacher be able to recognize good technical skills, reinforce those skills, and help to correct bad ones.

Like any other subject, good dancing skills are developed through practice, practice, and more practice. There is no shortcut to skill. There is no substitute for spending many hours working.

Coordination

Coordination is moving various parts of the body smoothly and with grace; this involves movement as an individual and with partners and/or groups. While a teacher should note and reward grace (good coordination), not all students have the same level of natural coordination. A teacher should identify awkward movement (lack of coordination) and provide activities to help students who struggle with this while not singling them out in front of others.

Balance

Balance in dance can mean several things:

- movement without falling

- keeping a dancer’s weight divided evenly between both feet

- standing on one foot without falling

These are some signs of a lack of balance:

- falling

- wobbling while moving

- flailing arms

There is also visual balance, which is the responsibility of the choreographer. Visual balance is creating an interesting picture on stage by arranging the dancers in compelling ways. Visual balance isn’t the responsibility of the individual dancers.

Kinesthetic Awareness

Kinesthetic awareness is knowing where your limbs are without looking. It is what allows us to walk without looking at our feet. Signs that a dancer has poor kinesthetic awareness are:

- looking at their feet while dancing

- watching their arms or hands while dancing

- arms or legs out of position

- body (trunk) at an odd angle

A beginning dancer may have to be gently reminded, “Don’t look at your feet; your feet will reach the ground.”

Spatial Relationships

We understand how objects and people move in relation to each other because we understand spatial relationships. Group dance is good for developing this understanding. Dancers should maintain spacing between dancers and take care to not bump into the scenery.

Time

Time is a strong, regular, and repeated pattern (it is sometimes called the “beat”). In this context, it refers to both the music and the dance. A dancer needs to “keep in time” with the music. It should be easy for a dancer to find and count the beat. Typical songs do not change their time throughout the entire piece. If they start in 4/4 (four beats to a measure), they stay 4/4 for the entire song.

Tempo

Tempo is the speed at which music is played, and the dancer follows the music. Beginning dancers should not be expected to dance to music that changes tempo or is too quick. A complicated dance piece might have two or three tempo changes in 10 minutes.

Rhythm

Rhythm is the pattern of the notes in a measure. A lot of quarter notes and eighth notes (quick rhythm) in a few measures might be followed by several measures with half notes or whole notes, which signal slower rhythm. Generally, each measure will have a different rhythm, meaning a different number and arrangement of notes.

A teacher/choreographer can “clap out the rhythm” so younger/beginning students can learn it. This is a common technique when teaching younger students. A beginning dancer/student should not be expected to follow a complicated rhythm.

Analysis

Dance analysis is used as a way to discuss and evaluate a dance. It can be used to evaluate the techniques/skills of the dancers. This analysis provides a basis for refining and improving a dance or evaluating a dance presentation by others. Analysis can be used for individual and group dances.

A dance teacher should be able to perceive and analyze dance, including responding to the following prompts:

- Describe the movement.

- What was the environment/atmosphere of the piece?

- What was the structure of the dance?

- How many parts were there?

- How did the parts relate to each other?

- How many dancers were in each part?

- Were there solo dancers?

- Describe the music.

- What was the lighting like before, during, and after the dance?

- What was the costuming?

- Were there any props used?

- Was there scenery?

By far, the most important part of dance analysis is describing the movement.

Interpreting Dance

“Interpreting dance” is asking, “What emotions were invoked?” “Interpretive dance” is dance specifically designed to tell a story and/or invoke emotions, which is not part of dance analysis. It is easy to confuse these two terms.

A choreographer plans a dance with intent and meaning:

-

The intent is the reason for doing the dance.

-

The meaning is the message and/or emotions that the choreographer wants to express and/or invoke.

Interpreting dance is a subjective activity. Each dancer brings something different to each performance, and each audience member will take something different from each performance.

Using Historical Context in Analysis

Dance styles and techniques have changed dramatically from century to century and vary from nation to nation and even from community to community.

Broadly, historical context refers to the world view and the social/economic environment at a specific moment in time in a specific place. The dance style of the Middle Ages is very different from modern dance; there is a much subtler difference between the dance styles of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Most dance historians can quickly spot the differences between dance styles of various eras and nations.

A dance teacher should demonstrate knowledge of a broad range of regional, community, and cultural styles and genres connected to the proper historical context.

All Study Guides for the CSET Multiple Subjects Test are now available as downloadable PDFs