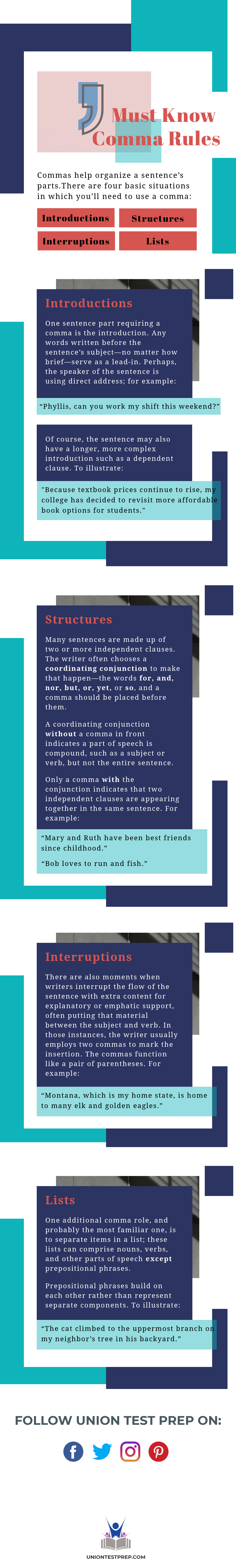

The ACT English Test: Must-Know Comma Rules

There are four basic situations in which you’ll need to use a comma: introductions, structures, interruptions, and lists. Each of these words denotes a purpose for the comma. It’s no wonder that writers feel overwhelmed about comma placement. However, one point is definite. Uncertainty should not lead writers to fall back on the “pause” method to accurately determine when to use this multi-purpose punctuation mark as it is not always accurate. Instead, remember: Commas help organize a sentence’s parts.

Introduction

One sentence part requiring a comma is the introduction. Any words written before the sentence’s subject—no matter how brief—serve as a lead-in. Perhaps, the speaker of the sentence is using direct address; for example:

Phyllis, can you work my shift this weekend?

Maybe he or she is opening with a prepositional phrase:

Long after sunset, the cowboy rode into town.

Of course, the sentence may also have a longer, more complex introduction such as a dependent clause. To illustrate:

Because textbook prices continue to rise, my college has decided to revisit more affordable book options for students.

In each of these examples, text (one word, a short phrase, or a dependent clause with its own subject and verb) prefaces the primary subject and verb (i.e., can you work, cowboy rode, and college has decided). Therefore, a comma appears immediately following the introductory word or passage so that readers can quickly ascertain the key point.

Structures

Many sentences are made up of two or more independent clauses. Again, the comma is the punctuation that helps establish the construction of a compound sentence. The writer often chooses a coordinating conjunction to make that happen—the words for, and, nor, but, or, yet, or so, and a comma should be placed before them. A coordinating conjunction without a comma in front indicates a part of speech is compound, such as a subject or verb, but not the entire sentence. Only a comma with the conjunction indicates that two independent clauses are appearing together in the same sentence. Let’s explore some examples:

Mary and Ruth have been best friends since childhood.

Bob loves to run and fish.

My cat is a creature of habit, for she always waits by her food bowl each morning for me to replenish it and then rolls over on her back for a belly rub.

Notice that the first two sentences consist of either a compound subject (Mary and Ruth) or a compound infinitive phrase (to run and fish). The third example, however, is a compound sentence (two independent clauses whose main components are cat is and she…waits) and includes a compound verb in the second main point (waits and rolls). A comma, however, only appears before the conjunction for since that is the only one connecting two independent clauses—clauses that could each stand alone as a complete sentence.

Interruptions

There are also moments when writers interrupt the flow of the sentence with extra content for explanatory or emphatic support, often putting that material between the subject and verb. In those instances, the writer usually employs two commas to mark the insertion. The commas function like a pair of parentheses. Here are a few examples of commas setting off text that interrupts the flow of the sentence:

My two-year-old, as you might imagine, is living up to the ‘Terrible Twos’ moniker.

Montana, which is my home state, is home to many elk and golden eagles.

The chief executive officer, herself, will speak at next month’s convention.

In the first two sentences, the subjects (two-year-old and Montana) are separated from their verbs (is living and is). Therefore, commas appear around the interrupting text, which could be omitted from each sentence without changing its meaning. The third example shows a reflexive pronoun. This type of pronoun refers back to the noun it is renaming for added stress. When the pronoun appears immediately following the noun it renames, it is set off with commas.

Lists

One additional comma role, and probably the most familiar one, is to separate items in a list; these lists can comprise nouns, verbs, and other parts of speech except prepositional phrases. Prepositional phrases build on each other rather than represent separate components. To illustrate:

The cat climbed to the uppermost branch on my neighbor’s tree in his backyard.

To the uppermost branch answers where the cat climbed; on my neighbor’s tree identifies the tree; in his backyard indicates the location of the tree. In other words, the sentence is not saying that the cat climbed three different places. Each phrase builds on the full description of the specific tree.

The ACT test abides by the Oxford comma rule. That is, insert a final comma in front of the conjunction and as you are adding the last item in your list unless the final two words denote one thing. Note the following examples:

In checking my baking supplies, I see that I need to buy flour, baking soda, and vanilla.

Two students from the fourth, fifth, and sixth grade classes are selected for recognition at the end of each month.

Please vacuum the living room floor, take out the garbage, start your homework, and order pizza for supper, since I will not be home until after 6 p.m.

When the woman came back from visiting London, she had a yearning for fish and chips, Yorkshire pudding, and bubble and squeak.

The first statement has a list of nouns that are objects of the phrase to buy. The second sentence provides a list of adjectives designating the grade levels, and the third sentence has a series of verbal commands. In the last example, however, a comma does not appear after the word bubble since bubble and squeak is the name of one dish.

Commas serve many functions within a sentence, but knowing that each comma is contributing to the overall organization and clarity of a sentence hopefully takes away some of the mystery and confusion about this “common” mark.

Keep Reading

ACT Blog

Essay Writing Practice and Prompts for the ACT

The ACT writing test is an optional exam, and is not always given as pa…

ACT Blog

How to Do Well on the ACT Essay

Understanding the ACT Essay Before diving into strategies to excel, it…

ACT Blog

How to Study for the ACT in One Week

Getting ready for American College Testing (the ACT) can be a source of…